Jan Yoors- a childhood wanderer, that left his parents’ home in Antwerp at the early age of 12 to join a group (‘kumpania') of Roma, who he travelled on and off with for ten years, and was eventually adopted by.

A life, that he wrote several books about and documented with timeless and brilliant black and white photographs.

Jan Yoors- an active member of the World War II underground, managing to escape from Gestapo capture and torture.

Jan Yoors- a polyamorous New York based artist, that reinvented the world of tapestry and hung around with Jackson Pollock and Willem De Kooning.

Jan Yoors- who had a relatively short life but continued to live on, in the epic designs he left behind. Extraordinary tapestries that were being created until years after his passing...woven on giant looms, by the two wives that survived and revered him.

At this point it’s hard to tell exactly how much of the details of his incredible story are true.

Jan himself once spoke the following words:

“Tapestry is by definition a mural art and as such can, and must, be of epic scale and heroic dimensions.”

And perhaps, he really lived a life that measured up to the exact same criteria as his art.

What I do know for sure though, is that he left a stunning legacy of paintings, drawings, designs, sculptures, books, photographs and tapestries. And for this post, I’d like to show a little more of the latter and about how and where they were created.

Design Process

After being inspired by an exhibition about French tapestries, Jan built a loom and together with his wives Annabert and Marianne, through trial and error, discovered the techniques of weaving.

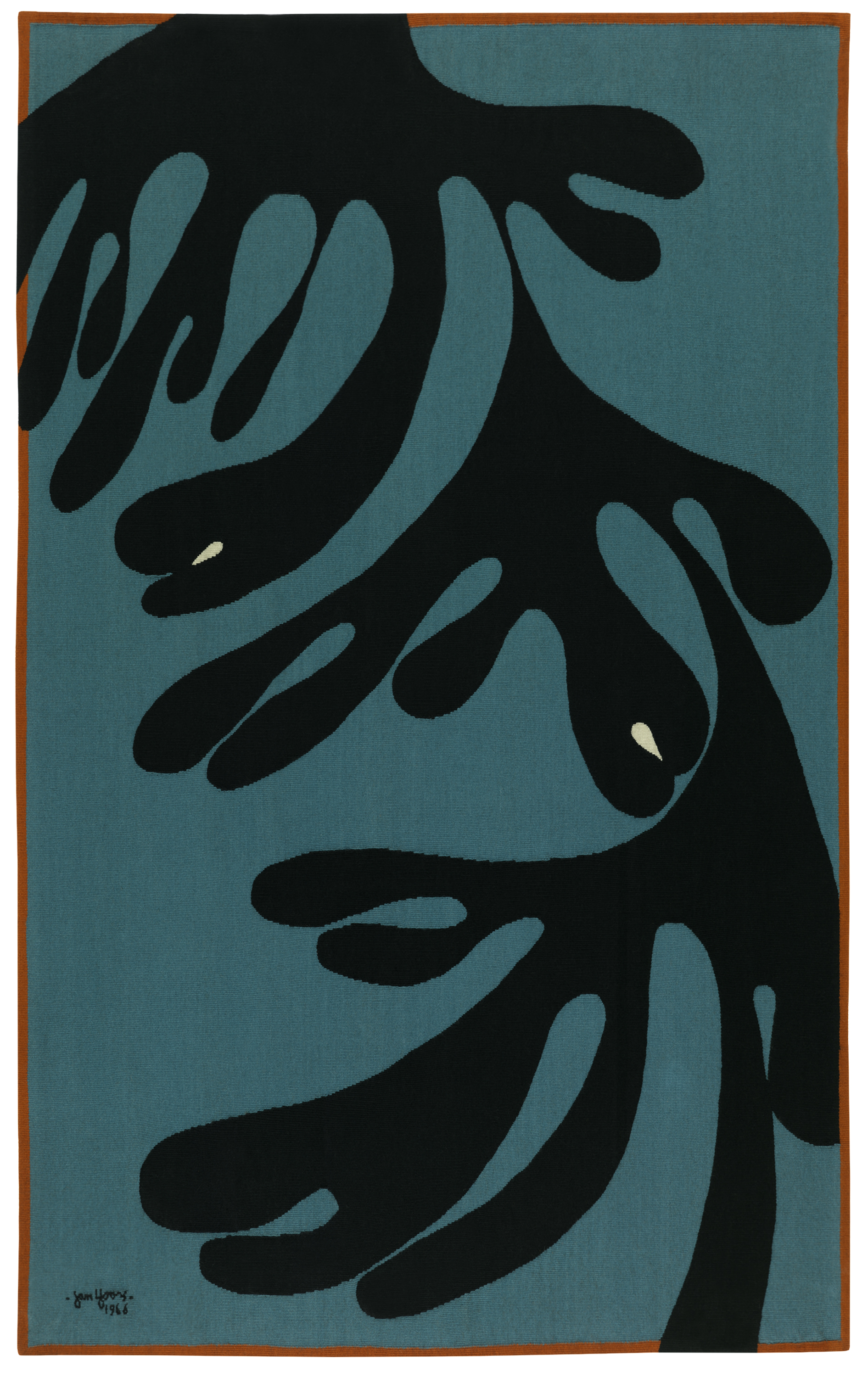

Then, after a decade of exploring vibrant figurative designs, often depicting biblical and mythical subjects, Yoors began designing abstract tapestries in the late 1950s. The abstract journey led him towards an increasing fascination with capturing the ephemeral and many of the tapestries from the late 1960s onward, recall geographic and natural forms, as well as more ephemeral concepts such as language.

“He would take a picture of a torn poster, a shadow or some graffiti—something that’ll be gone in a second—and then turn it into a design for tapestry, which would take ages to weave!”

- Kore Yoors about his father Jan.

This captivation with the ephemeral- and transforming its fleetingness through the permanence of an ancient art form as tapestry- is, where the timeless magic of Yoors’ designs springs from.

Surroundings became opportunities and inspiration became boundless- Jan, Marianne and Annabert all participated in this process and there was a constant dialogue and experimentation between them.

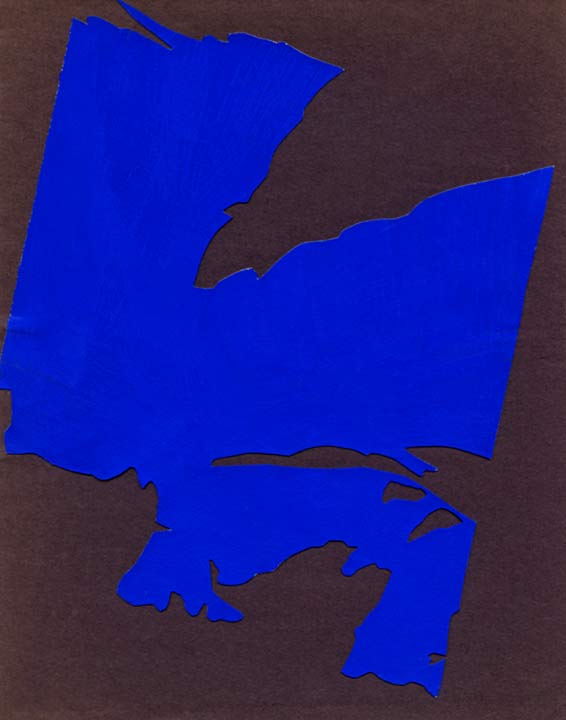

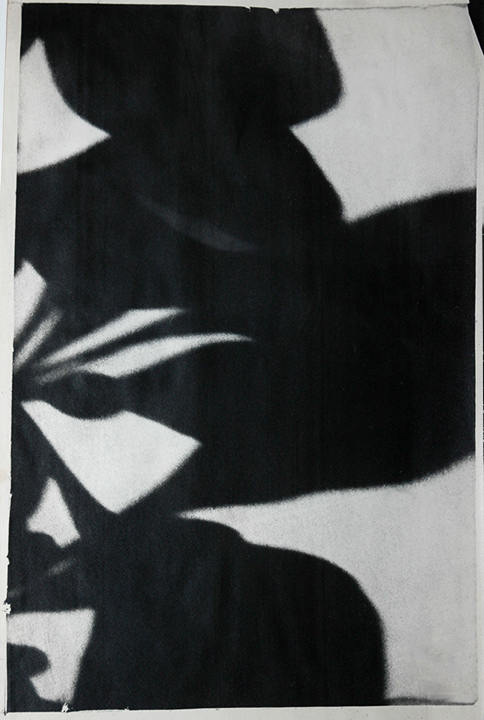

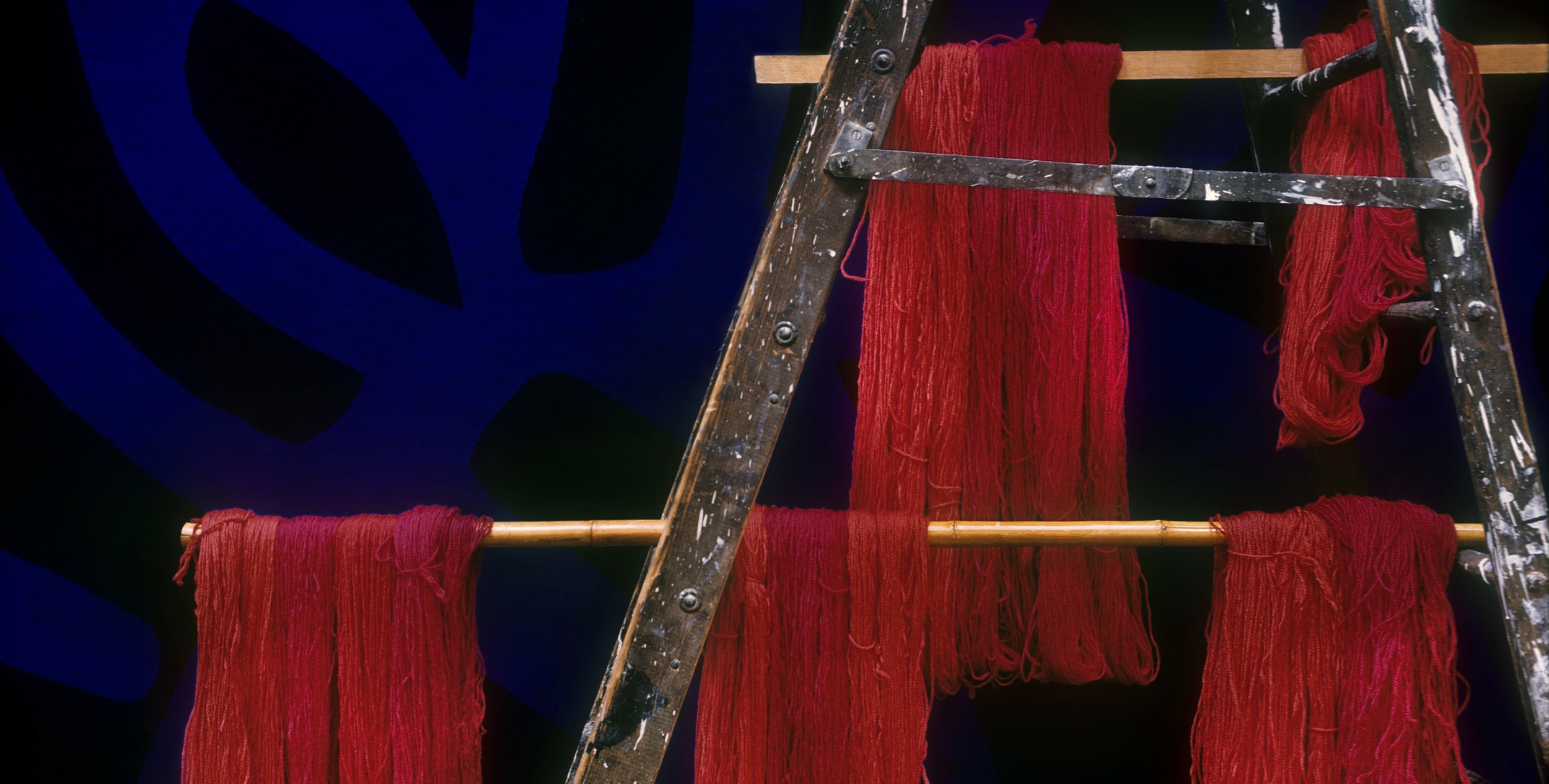

Through photography, the art form that already guided him on his journeys as a teenager and young adult, Jan could capture ephemeral elements such as patina and imperfections in urban landscape- like torn posters or dripping paint.

He would then rotate, crop and enlarge parts of the abstract photographs, and turn them into vibrant gouache designs.

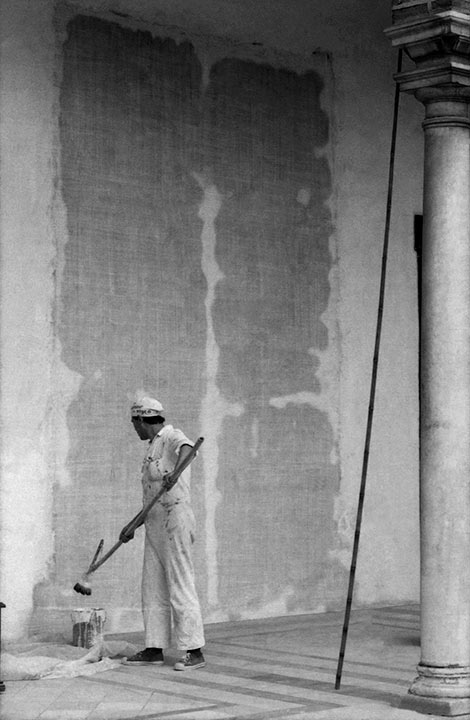

The gouache image was traced and gridded, to enable translation to a large scale that was transferable to their giant, hand built loom.

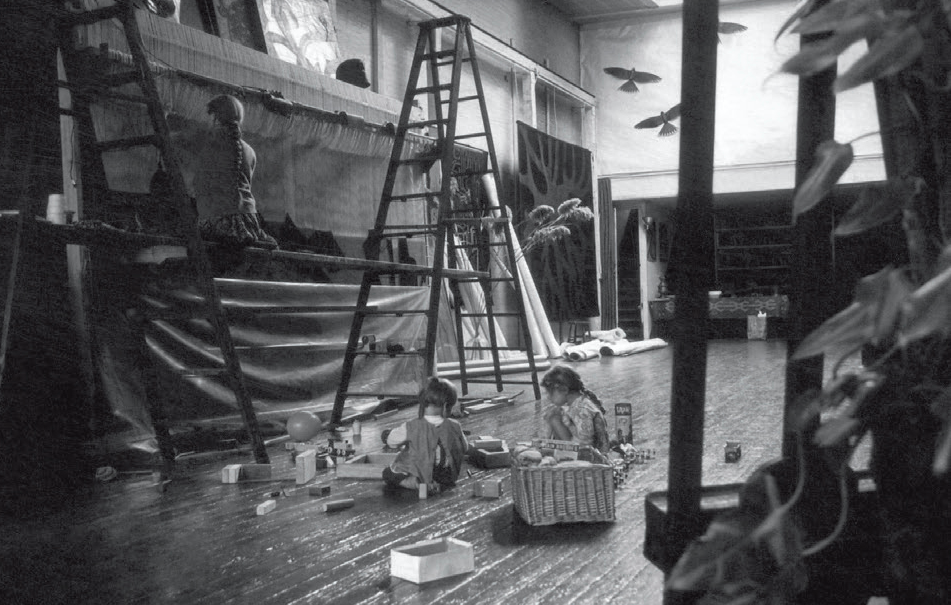

These full scale paintings were often hung behind the loom, for guidance while weaving and the warp threads themselves were painted on to mark changes in colour.

Process steps of designs based on photographs of landscape and of the residue of torn posters (click to enlarge):

Process steps of the tapestry “As Clouds to Moon”, based on Newspaper Cutouts:

Photographs of torn posters and Gouache designs:

Process steps of designs based on Shadow Studies:

Yoors designed The Tantra series from cropped contact prints that he made of leaves and their shadows.

Process steps of designs based on Texture and Pattern:

Weaving Process

If three to four people weave eight hours each day, a 2.5 by 3 metre tapestry, would usually take four or five months to complete.

When this sinks in, one can imagine that the lives of the Yoors family were inseparable from their work.

Annabert and Marianne wove together for fifty years, sometimes for days without a break.

Using an age-old method, they threaded their giant 4.5 metre loom and carefully transposed Jan’s original full-scale design onto the threads with a paintbrush.

They wove one colour at a time, beating each individual Persian thread down with a screwdriver. Marianne has said that they wove as one person, which is proven by the tapestries’ flawless surfaces.

The final product was hemmed and pressed, all by hand.

“When you spend six, eight, ten months weaving a tapestry, you weave a foot or so and roll it up.

You cannot make a mistake because it cannot be fixed.”

- Marianne Yoors

From each design, only one single tapestry was woven.

”We make one single tapestry from each design, as opposed to the current trend of producing editions or series of reproductions.

In an age marked by either anonymous mass production or, in its very opposite, what I consider, excessive egocentrism and interpersonal distrust, the team work, demanded by the making of tapestries as we practice it, is one of the purest forms of romance and personal fulfilment.”

- Jan Yoors

The tapestries were always signed, “Jan Yoors.”

In answer to the question why she and Annabert didn’t sign the weavings, Marianne has simply stated: “we signed with every stitch.”

96 Fifth Avenue

The Yoors’ moved to 96 Fifth Avenue in New York in 1950.

With tapestry not yet being recognised as a fine-arts form, plus it taking them six to nine months to weave one tapestry, they were completely broke.

“We had no money at all. We were living in a loft building we were not allowed to live. We had no kitchen, no bathroom... But all that mattered to Jan was having space to do his work.

The three of us worked every single day, even weekends, until midnight.”

- Marianne Yoors

329 East 47th Street

Their dedication however persisted and commissions started coming in, which then allowed them to move to a larger (and amazing!) studio on 47th street.

108 Waverly Place

Finally, in 1967, the Yoors Family ended up in Greenwich Village.

Jan and Annabert already had two children together (Vanya and Lyuba) and after Marianne became pregnant with Kore, they decided to divorce.

This was a formality, which enabled Jan to now marry Marianne and become Kore’s official father.

“I didn’t care about this at all, but Jan insisted!

We didn’t even have a celebration. We just went to City Hall, and that was it. I can’t even remember the date!”

- Marianne Yoors.

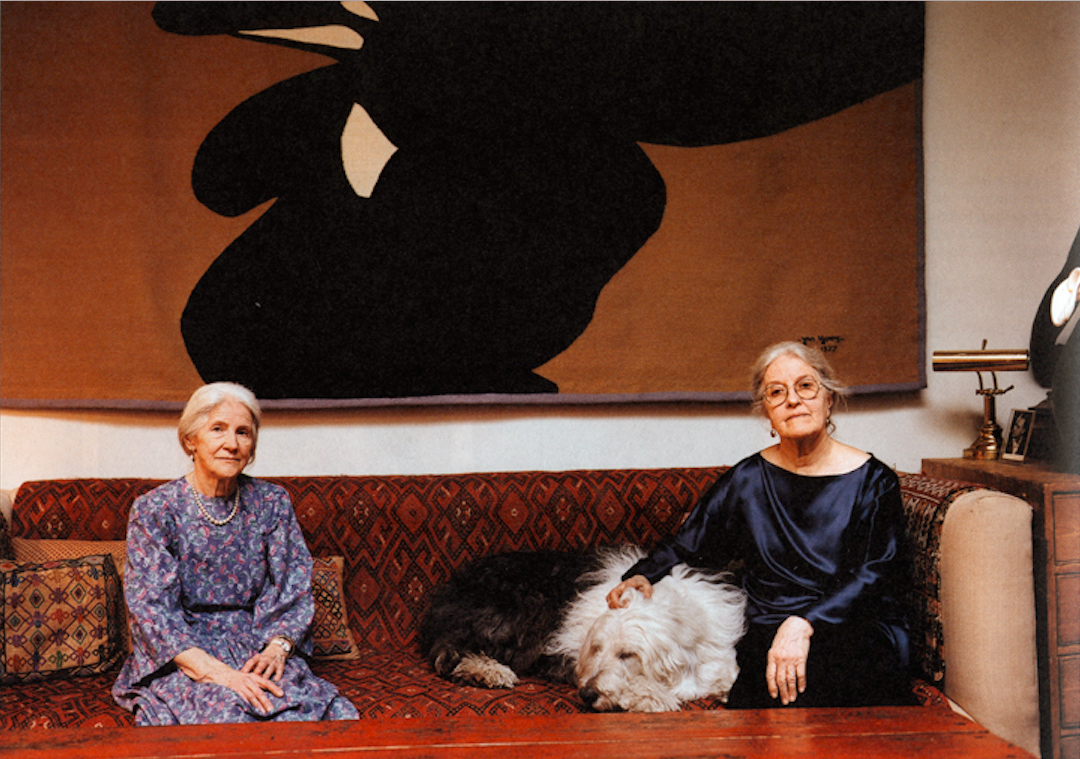

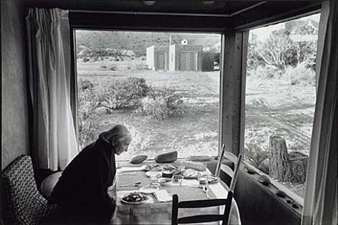

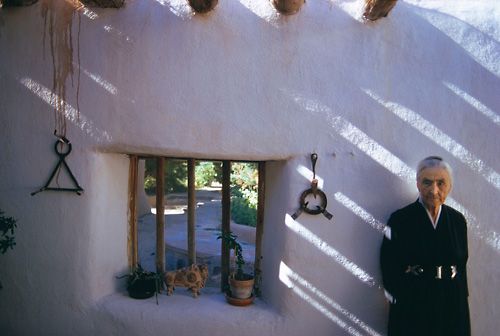

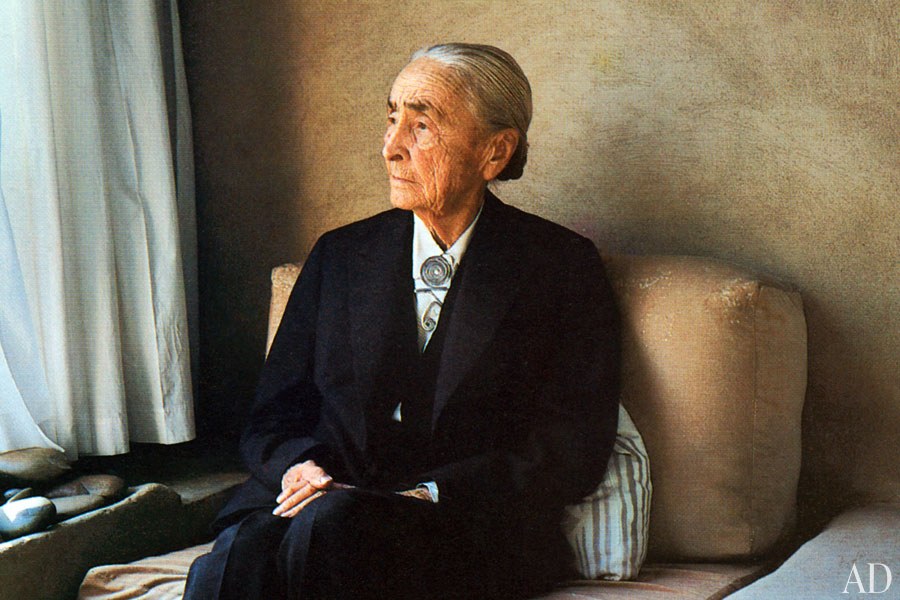

Apartment Kore and Marianne

Jan passed away in 1977, he was 55 years old and suffered a heart attack at home.

Annabert and Marianne continued weaving his remaining unwoven designs for many years, until the landlord decided to sell their studio.

In 1998, after 35 years, they had to leave Waverly Place for a much smaller apartment, where it became almost impossible to continue the weaving.

When asked the question by the New York Times if moving would be like disassembling a shrine, Marianne answered:

''That is the wrong word. A shrine is to something that is no longer alive.''

In the same interview, the ladies spoke about each other:

''She talks so beautiful,'' said Annabert of Marianne,

''She goes everywhere, she is afraid of nothing'' Marianne said of Annabert.

Annabert passed away in 2010.

Marianne and Kore still live in the smaller but beautiful apartment.

The space is unique and full of love and art, in the living room a coffee table made out of their first loom, throughout the house Mariannes wonderful ceramics an Jan’s timeless photography, life sized sculpture and vibrant designs.

Work

Jan, Annabert and Marianne Yoors created dozens of handwoven tapestries between 1945 and 1977, the year that Jan died.

The actual number is now closer to 200, seven of which have a length over 6 metres. The designs and colours are as brilliant and unique today as when they were first dyed and created.

But instead of speaking further about his art, let’s finish up with Jan’s own words:

“If I am reticent to speak about the sources, the drive to make, or the meaning of my tapestries, it is because I strongly feel that were I able to do so, articulately and coherently, I would be a writer on art rather than an artist.”

xez

*Photographs sourced from various locations, but mainly through the Yoors Family Partnership, please click pictures to enlarge.

Kore and Marianne’s apartment photographed by Leslie Williamson.